Bringing the Bald Eagle Back

Until last year, my mother had never seen a Bald Eagle in the wild. And this despite growing up in Westchester County’s river towns, being from a family of road trippers and beach goers, and ultimately becoming a mother who took her children hiking and camping all over the Northeast. In her lifetime, our national bird has gone from a maligned pest targeted by hunters for its (alleged) snatching of children and livestock to one of our proudest conservation success stories, with a population of approximately 316,000 birds in the lower 48 states as of 2021.1

How did we get here?

Prior to contact with European settlers, the Bald Eagle was a common bird, revered as a spiritual messenger as part of many indigenous belief systems across the continent. Eagle feathers still form an essential element of ceremonial regalia. Collection by tribal members remains protected by law as indigenous peoples continue to revive and practice their cultural traditions.

At the same time that the Bald Eagle was becoming enshrined as a symbol of American democracy, it was also being hunted, trapped, and poisoned to the brink of extinction. Persistent rumors of eagles swooping off with lambs and young children placed a target firmly on their broad brown backs.

Eagles gained a bad reputation on the basis of a misconception: despite being symbols of righteousness and integrity, Bald Eagles are scavengers by biology. These large birds notoriously prefer to snatch fish from the grasp of osprey over doing their own fishing. They have been known to chase coyotes, otters, and bobcats off their kills and push vultures from their carrion finds. They are, in short, opportunistic avian bullies. However, they are not capable of carrying more than a few pounds, ruling out most lambs and human children.

After World War II, the shift to industrial agriculture and growing reliance on chemical pesticides were very nearly the nail in the Bald Eagle’s sizeable coffin. DDT may have been very effective at killing unwanted insects, but worked its way up the food chain with devastating effect: apex predators like Bald Eagles laid eggs with thin shells, which they inadvertently crushed while incubating. By the mid-twentieth century, populations of Bald Eagles had cratered. In 1963, only 417 nesting pairs remained in the entire country.2

Thanks to advocacy like the 1962 publishing of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, the first Endangered Species List in 1966, and the fight for passage of the Endangered Species Act, DDT was ultimately banned in 1972. The picture began to improve, but the Bald Eagle had a long way to go.

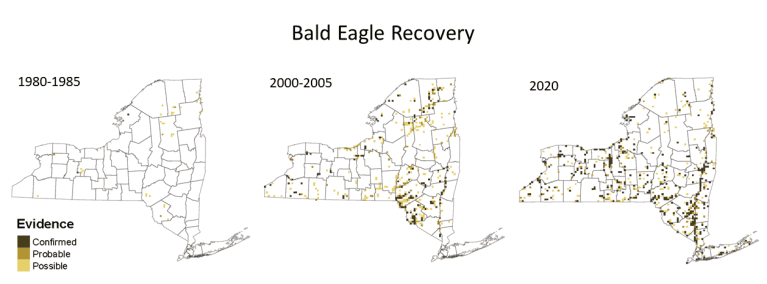

The situation in New York state was particularly grim. In 1960, only a single pair of breeding eagles remained. The New York State Bald Eagle Restoration Program3 began in 1976 by importing 200 nesting birds from Alaska, hand-rearing their chicks while carefully keeping them wild, and releasing them in Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge. By the program’s conclusion in 1989, ten pairs had established nests that they faithfully returned to every year. The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation continues to monitor Bald Eagle nests and happily reported 426 nest sites in 2017.4

On the strength of this work and similar projects across the country, the Bald Eagle was removed from the Endangered Species List in 2007. Fans far and wide continue to monitor its success through efforts like the third New York Breeding Bird Atlas, currently in year three of five years of data collection. Atlassers report Bald Eagles breeding across the entire state.

I just participated in the National Audubon’s 123rd Annual Christmas Bird Count on Teatown’s behalf. At one point, we had four eagles directly above us at once. It still feels magical to see these birds en masse. To find out when they’re on the move or to explore recent sightings, check out Audubon’s Migration Explorer and eBird listings.

My mother was nearly beside herself last winter when she spotted a pair of adults soaring overhead at the Edith G. Read Natural Park and Wildlife Sanctuary in Rye. Every time we went for a walk there, she was my good luck eagle spotting charm. Seeing them doesn’t get old.

Have your own magical moment with Bald Eagles at Teatown’s 19th Annual Hudson River EagleFest on Saturday, February 4. Tickets and more information at teatown.org/eaglefest

1 https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Bald_Eagle/lifehistory

2 https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/bald-eagle-fact-sheet.pdf

Leave a Reply